Two years on after the introduction of e-hailing legislation for cars, the Malaysian Government is now a facing a similar dilemma in coming up with legislation for bike e-hailing services or “bike-hailing”.

Bike-hailing in Malaysia

Anyone who has travelled to Indonesia, Vietnam, or Thailand would know that it is commonplace to see ‘motorcycle taxis’, as it is locally termed, zipping around inner-cities. Even before the proliferation of e-hailing apps, they have been an integral part of daily life. In fact, it is unsurprising that studies reveal these three countries have the most motorcycles in the ASEAN region with Indonesia at an estimated 109 million, followed by Vietnam at an estimated 54 million, and lastly, Thailand at an estimated 21 million.

Malaysia, a country with an estimated 13 million motorcycles, experienced its first foray with bike-hailing through local pioneer, Dego Ride who introduced the concept in late 2016. At that point in time, Dego Ride operated through a SMS system to confirm bookings and appointments. In December 2017, the Ministry of Transport declared Dego Ride as illegal and ordered them to cease operations, citing safety as the primary concern. An analysis done by the Ministry of Transport suggested that fatal accidents involving motorcycles were 42.5 times higher than that of buses and 16 times higher than that of cars.

However in August 2019, Cabinet through the Youth and Sports Minister, YB Syed Saddiq, announced that the Government would relook into the feasibility of allowing bike-hailing in Malaysia in support of job creation. Concurrently, a Government agency, the Malaysian Institute of Road Safety Research (MIROS) initiated a survey to gauge road consumers’ perceptions on the viability of bike-hailing services, the findings which would be presented to the Ministry of Transport to outline the mechanism for implementation. The Minister of Transport, YB Anthony Loke also announced that the Ministry had until the end of September to present a paper to the Cabinet on the mechanics of introducing the bike-hailing service in the country.

Benefits and Concerns relating to bike-hailing services

Since the announcement to introduce bike-hailing services, there have been multiple concerns on the implementation of bike-hailing and whether it should be allowed. Nonetheless, it is important to note that the implementation of bike-hailing services will also bring about benefits to the Government, industry, and the public. The table below sets out a comparison of the general concerns and benefits relating to bike-hailing services for various stakeholders.

| Parties | Benefits | Concerns |

| Government | • Generate income as the riders and operators will be imposed with licensing fees and taxes. • In line with Government’s effort to help the B40 group as motorcyclists and pillion riders. | • Insufficient enforcement personnel to regulate bike-hailing services. • Corruption among enforcement officers. |

| Industry | • Creates a level playing field between bike-hailing services and other forms of public transport services, particularly taxi services. | • Creates more competition for the taxi industry who is already facing competition with the emergence of e-hailing services. • Competition between new local bike-hailing operators against experienced foreign bike-hailing operators. |

| Public | • Provides convenience for riders wanting to travel short distances. • Provides job opportunities to the B40 group and youth. • Lower fares imposed and faster transport in comparison to other public transport services. • Provides accessibility to rural areas that can only be accessed via footpaths, tracks and small roads. | • Perception that bike-hailing services are generally unsafe, anarchic and inappropriate means of public transport.

|

Existing legal framework and regulatory trends in relation to bike-hailing in the ASEAN region

Bike-hailing is already a popular form of transportation in various emerging ASEAN economies. As a result, many countries have either some form of pilot project initiative, legal framework, or allow bike-hailing without explicit Government regulation. The table below sets out the status and information on bike-hailing laws in some of the neighbouring ASEAN countries:

| Country | Status | Updates |

| Indonesia | ✔ Regulated by Regulation Number 12 of 2019 concerning the safety and protection of users of motorcycles used in the interest of the community (“Ojek Regulation”). | ✔ Ojek Regulation was officially enacted on 11 March 2019 but there are different dates of enforcement for different regions, starting from 1 May 2019. ✔ Since 1 May 2019, the Ojek Regulation has already been enforced in Jakarta, Bandung, Yogyakarta, Surabaya and Makassar. |

| Vietnam | ✔ In the process of enacting a law on bike-hailing services. | ✔ The Vietnamese Government allows and encourages bike-hailing services to operate in Vietnam as it benefits the consumers and drives Vietnam towards Industry 4.0. ✔ Hanoi has launched a five year bike-hailing pilot program to run through 2021, which includes participation from 10 companies. This program allows the companies to offer bike-hailing apps in Hanoi, Danag and Ho Chi Minh City and the provinces in Khanh Hoa and Quang Ninh. |

| Thailand | ✔ In the process of enacting a guideline on bike-hailing services. | ✔ Thailand is the first country to ever regulate motorcycle taxi services and it has comprehensive regulation in relation to motorcycle taxi services. However, there is yet to be a bike-hailing regulation to regulate the new business model. ✔ To date, Thailand has drafted a guideline to regulate bike-hailing operators and expects to legalise the service by March 2020. |

| Phillipines | ✔ In the process of enacting laws for bike-hailing services. ✔ There is an ongoing six-month pilot project with Angkas, a bike-hailing operator in the Philippines that has started since end of June 2019. | ✔ On 4 February 2019, the lawmakers approved a House Bill on bike-hailing services. ✔ Sometime in March 2019, the Department of Transportation (DOTr) approved an official motorcycle taxi pilot with Angkas to assist in the law making process.

|

| Cambodia | ✔ Not regulated. | ✔ The Cambodian Government has allowed local and international bike-hailing operators to operate in Cambodia. Nonetheless, there is no law to regulate bike-hailing service in Cambodia. |

| Singapore | ✔ Prohibited. | ✔ According to a statement made by the Singapore Land Transport Authority, motorists are not allowed to ferry passengers for hire and reward. Therefore, it makes the service by bike-hailing operators illegal in Singapore. |

| Myanmar | ✔ Not regulated. | ✔ Contains presence of both local and international industry players including HelloCabs, Oway Ride and Grabbike that are not regulated. |

| Brunei | ✔ Not regulated. | ✔ – |

| Laos | ✔ Not regulated. | ✔ Motorcycle taxis have been in the Laos’ market since 2010. ✔ An example of a bike-hailing operator in Laos is VaiVai Taxi Laos. The company provides taxi, tuk-tuk and bike-hailing services. |

Bike-hailing framework in Malaysia

On 5 November 2019, the Minister of Transport, YB Anthony Loke, announced that the Government would allow bike-hailing operators to provide services through a pilot project or ‘Proof of Concept’ (“POC”) for a period of six months beginning January 2020. The POC period will allow the Government to collect data on bike-hailing relating to among others, safety and demand, while giving time for the Ministry to develop relevant laws on bike-hailing.

Together with the announcement, the Minister of Transport also outlined several features of the potential bike-hailing framework. Below is a summary of the key features of the potential framework together with a brief commentary of issues to be considered:

- First and last mile connectivity

First and last mile connectivity is the hallmark of the Malaysian bike-hailing framework.

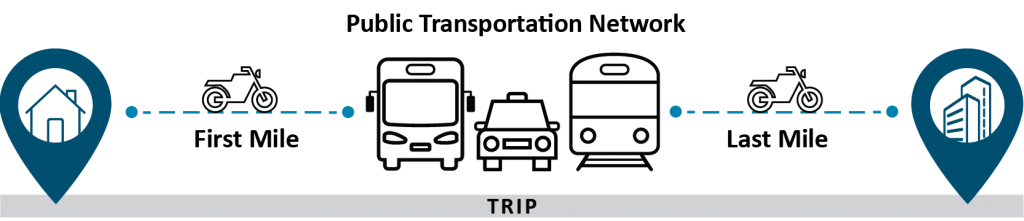

In transportation terms, first and last mile connectivity essentially means that bike-hailing services can only be provided from a passenger’s starting point to the pickup point of the public transportation network (first mile) and from the drop-off point of the public transportation network to the passenger’s final destination (last mile). This is illustrated below:

In order to further entrench the first and last mile connectivity feature, bike-hailing services would also be limited to a certain radius, possibly within three to five km of the public transportation network, in order to ensure that this form of transport is not abused together with concerns on ‘highway rides’. In other regulatory regimes, this is not the case as Indonesia and Philippines allow long distance travel for bike-hailing services with no cap on the maximum distance for every ride. Hence, it is common for riders in these countries to travel up to 20km per ride for their passengers.

Another contention in support of the first and last mile connectivity feature is to ensure that it does not overlap nor compete with other forms of public transportation in operations such as trains, buses, taxis, and e-hailing to name a few. This would mean that although bike-hailing services would be allowed, there would be minimal interference with the existing public transport framework as bike-hailing would instead complement existing initiatives.

- Area of POC

The POC announcement limits bike-hailing services to operate in the Klang Valley area only, while the law is being developed. At the same time, the Government has recognised that the POC may be extended to other areas if there is a demand. It is important to note the importance of holistic testing in affecting the data and statistics to be collected for the purpose of developing a national-level bike-hailing framework given the nuances of different localities.

For example, the pilot project in the Philippines was undertaken in two different cities, Metro Manila and Metro Cebu, both which are distinctly different in characteristic, density, and population size. In Indonesia, understanding of these localities has led to the Government implementing different fare matrix in different ‘zones’ where the more urban area of Greater Jakarta in Zone 2 has a lower price floor and price ceiling as compared to rural areas such as Sulawesi, Nusa Tenggara, Maluku, and Papua in Zone 3.

Expanding the scope of the POC is important in understanding the different challenges and demands of bike-hailing services in the various cities, towns, and even villages nationwide. This is relevant especially where motorcycles are arguably considered the primary form of transportation in Malaysian rural areas such as villages in which the implication of bike-hailing laws has not been fully appreciated. Unless the Government is taking the approach to limit the service to major cities for the time being, there is a need to ensure feasibility and applicability of the legal framework not only in the Klang Valley but also to the sub-urban or rural areas.

- Rider and passenger requirements

A requirement imposed on riders and passengers in the proposed framework is that riders must be eighteen and above and ferry only one passenger at a time, who must also be eighteen and above. This is somewhat different to the approach taken in other countries such as Indonesia and the Philippines. In Indonesia, there is no age limit, while in the Philippines the rider may reject passengers below the age of seven years old. Nonetheless, it is evident that the age limit requirement operates in mitigating the higher risk of bike transportation associated to those who have achieved the age of majority or are considered as adults.

A related concern that has yet to be mooted is the issue regarding opposite gender rides being female riders ferrying male passengers or vice versa. This issue has been at the forefront of criticism in our Muslim majority country, attributed to the close proximity that this form of transport inevitably entails. Interestingly, our neighbour Indonesia, with an even larger and sizeable Muslim majority, is more liberal and does not share the same sentiment on opposite gender rides.

One best practice can be seen in the Philippines, where the rider must wear a body or vest-based strap or belt that can be held by the passenger in case he or she feels uncomfortable holding on to the rider’s waist. This practice, although not ideal in resolving the issue of close proximity of rider-passenger on motorcycles, provides an alternative to minimise physical contact. It is also noteworthy to mention that in the Philippines there is a requirement for compulsory Passenger Courtesy Training that has a module on sexual harassment which includes, among others, the ways to avoid sexual harassment, and treating passengers with courtesy and respect.

Ideally, the Government should undertake a robust public consultation in tailoring a solution to address this issue, similar to the efforts made by Dego Ride in engaging, among others, Islamic religious leaders in 2016 before proposing a solution. In that case, stakeholder feedback indicated passenger preference to be limited to same gender rides, where statistically 70% of Dego Ride passengers happened to be female.

- Safety requirements

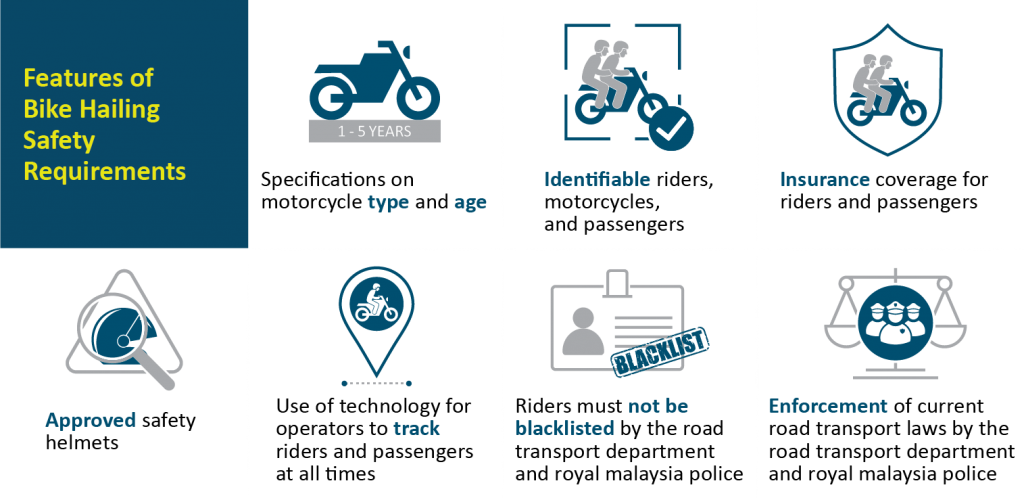

There are various features relating to safety requirements that have been outlined under the model framework which include among others the following.

The above evidences general safety requirements and standards which are typically expected to be imposed on bike-hailing services. However, as with any emerging industry, it is important for the Government to continuously understand the ever-evolving safety concerns and risks associated. As an example, in Indonesia the Government has made it a point to continuously address the concerns of the public by having a “community participation clause” in its laws whereby the public is encouraged to among others provide input to improve the laws on bike-hailing for the “safety and benefit of the community”. Similarly in Malaysia, it would likewise be prudent to provide for flexibility for disruptions in the bike-hailing framework and to periodically revisit the model law post-implementation to ensure it achieves the regulatory objectives.

- Operator requirements

At this juncture, little is mentioned on the requirements to be imposed on bike-hailing operators. A fundamental concern would be on whether the service would be open to foreign operators, although the Transport Minister has openly invited foreign operators such as Go-Jek to apply. To date, the only requirement indicated for the POC is that operators are to be registered with the Companies Commission of Malaysia, which means that operators have to be locally incorporated entities. The question then is whether there would be any foreign equity restrictions imposed on bike-hailing services in Malaysia.

It is not surprising to see foreign equity restrictions imposed on certain businesses to encourage, guarantee, and protect a certain number of local participation in an industry. In countries such as the Philippines, equity restrictions are imposed on public utility companies, where 60% of such companies have to be locally owned. Similarly in Indonesia, foreign ownership of non-route transportation companies is limited to 49%. In Malaysia, the position remains to be seen. However, with the announcement that the laws would be ‘similar to e-hailing’, it looks likely that some form of foreign restriction either through local shareholding and/or local Board representation would be imposed.

- Fares

Another point of discussion is on whether there would be any controls imposed on fares. Questions that are frequently asked revolve around the notion of whether there is a cap on surge prices, being the maximum increase in fares that can be charged during peak hours and whether the fare matrix is prescribed by the Government. This approach is mirrored in the Philippines and Indonesia where the Government has prescribed fares in consideration of among others distance travelled and population density.

For businesses, the preference would be for Governments not to regulate and allow market forces to dictate prices in determining the commercial viability of the industry. If e-hailing is anything to go by, this would likewise be the approach for bike-hailing in Malaysia where surge prices are capped but fare matrix is dependent on market demand. However, a notable concern with this approach is that although operators and passengers would benefit, the one at the losing end may potentially be the riders.

It is important to have an extensive engagement on the topic of fares as such issue transcends the traditional notion of operators’ commercial profitability but also involves stakeholders such as the income to the riders and expenditure of the passengers. This discussion is especially pertinent at the present time given the ongoing debate and uncertainty about workers’ rights in the gig economy. If the objective of job creation in legalising bike-hailing is to be achieved, there is a real need to ensure the appropriate fare model is implemented which does not ultimately jeopardise the livelihood of riders.

- Key Performance Indicators

Last but not least, is the lack of key performance indicators for the pilot project which have yet to be outlined. This may prove to be a double-edged sword as the lack of transparency could stifle the development of the law should there be, among others, a sudden change in political interest in the matter. For one, the POC should be geared to test and resolve the overarching concerns relating to bike-hailing services, which the paramount concern has always been pertaining to safety. Lessons can be learnt from the model in the Philippines where the accident threshold is the primary barometer followed by traffic rules violation and finally, customer feedback in analysing the success of the pilot project towards developing a model law.

The key performance indicator is necessary in not only overcoming safety issues but also to gain trust and confidence from the public to use bike-hailing services. This ties back to the fact that Malaysia is dissimilar from Indonesia, Vietnam, or Thailand, who have been utilising bike-hailing services for years. Once the key performance indicators are published, the public can gauge for itself whether to use the service or not. For example, if the key performance indicators are not met due to safety inadequacies, bike-hailing operators would naturally invest in safety mechanisms above and beyond the minimum standard to win public confidence. Key performance indicators can consequently be used as positive measure in maintaining transparency and boosting confidence for all stakeholders in the industry during the development of the bike-hailing laws.

Conclusion

After much scrutiny, the Government has in principle agreed to introduce bike-hailing laws upon satisfactory completion of the POC. At the same time, the features of the proposed regulatory framework that have been announced appear at best to be the building blocks of the proposed law. This is an indication of the country’s lack of experience in dealing with this issue compared to economies with prevalent motorcycle usage such as Indonesia, Vietnam, and Thailand. The initiative is commendable as it balances the need to develop policy and obtain information on the impact of bike-hailing with the willingness to allow limited operations in a regulatory sandbox model. At the same time, a more organic model can be home grown once input from a Malaysian context is obtained from the POC.

However caution must be heeded especially when regulating unfamiliar territory. Although bike-hailing is similar to e-hailing, it is fundamentally important not to overlook the differences and apply a one-size fits all policy in regulating both forms of services. It is also crucial to understand the ever-evolving nature of the sharing economy and the complex roles of the players involved, that is, regulators, operators, riders, and passengers, in creating smart regulation. In addition and once the framework is developed, the implementation plan needs to be properly considered and executed in order not to replicate the roll out issues seen with e-hailing implementation. Lastly, it needs to be highlighted that the present discussion is only on bike-hailing transportation; and has yet to extend to other bike-hailing services such as food, logistics, and courier services which remain unregulated.

Inevitably, arguments against bike-hailing will always point to safety concerns and the higher risks compared to cars and buses. To balance this and devise an all-inclusive policy, the Government must ensure consultation with a comprehensive range of stakeholders. This means not only the typical interactions between the regulator and the regulated, but also the general public who will be end-users of the service and dictate the viability of the business. Although the altruistic intention of introducing bike-hailing by the Government is to provide a comprehensive public transport system in the country, the risks need to be carefully weighed. And who better than the end-users who will ultimately determine whether such risk is outweighed in favour of cost and convenience. As summed up by the Prime Minister Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad himself, “If you feel it is not safe, don’t use. We have a choice and we are not forcing you to take the motorcycle ride”.

If you have any questions or require any additional information, please contact Mohamad Izahar Mohamad Izham or the Zaid Ibrahim & Co. partner you usually deal with.

This alert is for general information only and is not a substitute for legal advice.